This labor-of-love should prove quite useful: http://vimeo.com/37120554

Lisa and “Lisa”

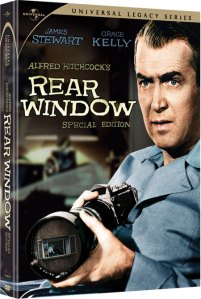

The new Legacy DVD edition of RW includes an interesting new documentary, The Sound of Hitchcock, in which sound designers and critics comment on AH’s use of music and audio in his films (the ones released on DVD by Universal, anyway). Several soundtracks are analyzed, but I found Gary Rydstrom‘s comments on RW particularly revealing. After some preliminary thoughts on the evolution of the song “Lisa” within the film, Rydstrom gets to the really choice bit:

So now we come to the end of the movie, and visually, this is a scene about Grace Kelly. Jimmy Stewart has wondered, you know, “Is she the girl for me? She’s a Park Avenue girl. Is she tough enough for me?” She breaks into Raymond Burr’s apartment, you know, the bad guy’s apartment when he’s not there, to get a clue.

From here on it’s just that song, which is called “Lisa.” This is the fullest expression of the song we’ve heard in the movie so far, the most complete version of the song that represents their love story. But what’s happening is that Hitchcock is showing us the part of the movie that’s a murder mystery. This is really suspenseful and painful to watch. The soundtrack is climaxing the love story, cause the song is telling us that Jimmy Stewart is now finally in love with Grace Kelly. But the disconnect is rich. If you have the soundtrack telling you one part of the story, and the visuals telling you another, there’s this richness that comes out of it, as well as a tension because the mood of the music is not the mood of what we’re seeing.

Perhaps even more to the point, we’re seeing the two threads of the plot finally meshing. The song ends as the police arrive and Lisa passes out of danger. Now all that remains is for Lisa to reveal the wedding ring—and by doing so, expose Jeff, for the first time, to Thorwald’s baleful gaze.

Posted in Uncategorized

DT on RW

David Thomson has just launched “Have You Seen . . . ?” A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films, a reworking of his famous The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. I got a copy and turned immediately to the entry on RW.

David Thomson has just launched “Have You Seen . . . ?” A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films, a reworking of his famous The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. I got a copy and turned immediately to the entry on RW.

Thomson is iconoclastic and opinionated, and can’t always be relied upon to endorse the received canon. But his write up of RW couldn’t be more favorable. It begins: “There are great films and great entertainments. Sometimes one film is both—take Rear Window.”

His final paragraph is also laudatory and concise:

It’s 112 minutes. It’s funny, tart, tender, thoughtful, desperate, and as neat and tidy a moral parable about looking at things and getting involved as you’re ever going to find. I suppose I’ve watched it forty times or so, and I’m still waiting for it to taste like less than a Meyer lemon fresh from the tree. But as time passes, the suspense falls away, and the bones of greater comedy emerge.

I don’t know whether Thomson is referring to small “c” comedy or comedy that begins with a capital letter, but either way he’s right. Hey, sometimes even iconoclasts find themselves traveling coach.

Posted in Uncategorized

If You’ve a Mind To, You Can Now Count Every Brick.

DVDBeaver weighs in on the new Universal Legacy series DVD. . . and the news is good.

Posted in Uncategorized

Back-door Use of a Rear Window

Posted in Uncategorized

Sorry, Wrong Window

Witness to Murder is about a woman  (Barbara Stanwyck) who looks out her window one night and sees in the facing apartment what she thinks is a murder. She contacts the police who investigate but find no evidence and so are skeptical. The woman decides to gather evidence on her own. Her activities quickly bring her to the attention of the murderer (George Sanders), who takes steps to shut her up. The film was released, as was RW, in 1954. Coincidence? The short answer is yes.

(Barbara Stanwyck) who looks out her window one night and sees in the facing apartment what she thinks is a murder. She contacts the police who investigate but find no evidence and so are skeptical. The woman decides to gather evidence on her own. Her activities quickly bring her to the attention of the murderer (George Sanders), who takes steps to shut her up. The film was released, as was RW, in 1954. Coincidence? The short answer is yes.

Now for the longer answer: both WtM and RW share a common antecedent. In The Window (1949), a boy can’t convince his parents—let alone the police—that he has witnessed a murder. Even earlier, Sorry, Wrong Number (1948), another Stanwyck picture, featured a woman in danger who has discovered a murder plot and whom no one believes. Another influence on WtM—if not RW—is probably Gaslight (1944), as part of Saunders’ strategy to avoid detection is to discredit Stanwyck by making her appear a mental case. He does his job so well he has even Stanwyck’s character questioning her sanity.

It’s interesting to compare and contrast WtM and RW. In WtM, Stanwyck’s character uses binoculars to study the murderer in his apartment across the way. Also, Saunders makes a late attempt on Stanwyck’s life. He visits her in her room and tries to throw her out her window, the very one through which she witnessed the initial crime. The film differs from RW in a number of ways, most notably in that there is never any doubt about the crime. Also, the film spends a lot of time with the murderer; long before we’re introduced to Stanwyck we see Saunders acting to avoid detection.

WtM is an entertaining film, with good performances, moments of suspense, and high-contrast B&W photography by John Alton (it was directed by Roy Rowland). But it doesn’t have Grace Kelly, the exploration of a mammoth single set, the witty dialog of John Michael Hayes, or Hitchcock’s deft direction. WtM is what you might expect Hollywood to produce after rolling out any number of woman-in-peril pictures. RW remains sui generis.

Posted in Uncategorized

Cameo, sham-eo

A hot topic of discussion over at the Hitchcock Wiki Forum recently was that AH may have made a second cameo in North By Northwest. Hitchcock is famous for appearing briefly in his films, and he’s often easy to spot. But he always restricted himself to just one appearance per film. The idea of a second cameo in any film–heresy! So controversial has this been, even the Telegraph picked up the story.

The recognized cameo is easily spotted and comes just as the opening titles finish: trying to board a bus, Hitchcock gets the door slammed in his face. The second cameo occurred–supposedly–later, on the train, when Cary Grant emerges after hiding in the restroom. Just visible down the corridor at that moment is a woman, sitting, whose profile bears a striking resemblance to the director’s. Hitchcock in a dress?

DavyP has the details here. But after examining the evidence, the conclusion he reaches is that it’s a cameo, all right, just not Hitchcock’s. It’s an actress named Jesslyn Fax, a veteran of many Alfred Hitchcock Presents episodes. Here’s the RW connection: she’s the woman who plays Miss Hearing Aid, the sculptress, seen napping at the end of the picture. Those cameos can be exhausting, I guess.

Posted in Uncategorized

The Birds

Not AH’s movie of the same name, but the caged creatures shown fleetingly at the beginning and end of RW. They don’t really do anything, but they’re there. Do they mean something?

Birds are frequent visitors to Hitchcock’s cinema, they perch in Sabotage and Foreign Correspondent, the sinister shadow of one hovers in a dream in Spellbound. If you care to stretch a point, there is even a giant, machine-gun-firing bird that menaces Cary Grant in North by Northwest. Famously, stuffed birds decorate Norman Bates’s inner office in Psycho. And of course, birds are the point of The Birds.

Birds are frequent visitors to Hitchcock’s cinema, they perch in Sabotage and Foreign Correspondent, the sinister shadow of one hovers in a dream in Spellbound. If you care to stretch a point, there is even a giant, machine-gun-firing bird that menaces Cary Grant in North by Northwest. Famously, stuffed birds decorate Norman Bates’s inner office in Psycho. And of course, birds are the point of The Birds.

There are those—let us call them motif mongers—who see all these birds about and shout, Symbol, symbol! They attempt to ascribe to the motif a single, unvarying association. And because the birds of The Birds are the most flamboyant members of their kind, visiting mayhem on humanity, your typical motif monger would have us believe birds in Hitchcock are always portents of death or destruction.

But not so fast, birdseed breath! The matter is more complicated than that. Let’s remember that even in The Birds there is a benign avian pair out of sync with their rampaging brothers and sisters. These lovebirds are present at the beginning of the film, and actually bring the hero and heroine together. At the end of the film, the lovebirds are retained, even as the couple are fleeing all the other birds. Clearly, there are distinctions to be drawn among birds.

Let us return to RW. I can’t tell how many birds are in the cage at the beginning of the film, but at the end there are two—at least, I’d like to think there are. Nothing malign can attach to these creatures. In fact, given the tenor of the film’s ending, might not the birds reappear at that point simply to share in the harmony and bliss that is building about the courtyard? Hmmm, what kind of birds are they, anyway?Are you thinking what I’m thinking?

Posted in Uncategorized

So, Where’s the Blu-ray Disc?

Universal Studios Home Entertainment has announced the upcoming release of a new special edition of RW–along with SEs of Vertigo and Psycho–due in October. Here’s the info from their press release. Continue reading

Universal Studios Home Entertainment has announced the upcoming release of a new special edition of RW–along with SEs of Vertigo and Psycho–due in October. Here’s the info from their press release. Continue reading

Posted in Uncategorized

Film Studies Kids These Days

Students last year at the University of Central Florida, having completed a documentary on RW for film class, put the fruit of their labor on YouTube for all to see. The piece is more clever than ambitious, however, as what they did was simply take an existing documentary (included on the current DVD release of RW), drop out all the commentary and shots of talking heads (film industry types opining), then put their own commentary and heads in place. Thus they achieved high production values for relatively low cost and effort.

Unless you’ve seen the original, the piece is pretty impressive. Still, for a student project, intended to demonstrate the knowledge the makers have acquired, it’s reasonably effective. But what is it the students have learned? Yes, Jeff is the protagonist, but guys, guys, no way is Lisa the antagonist–that’s Thorwald (Lisa, if you wish, can be labeled the deuteragonist). And I can’t believe some of the things coming out of the mouths of these 20-year-old kids: Jeff feels he’s too “inadequate” to have Lisa as a girlfriend or wife; RW is the first film to present a voyeur as its hero; one of the concerns of RW is feminism. Where are they getting this stuff? Not from the film, that’s for sure.

Posted in Uncategorized